Japanese Animation and New Media

Week Six: Chapter Ten: Structures of Depth

Now, as many commentators have noted, the conceptualization of superflat gain its sense of flatness through the elaboration of a sharp contrast with a specific structure of depth, that of one-point perspective. As we have seen, one-point perspective is not a neutral set of techniques. It brings with it conventions and associations that have made it central to a regime of modern visuality called Cartesianism, which implies a specific set of material orientations and rationalized relations between subject and object, viewer and world. Thus, when superflat is contrasted with the depth of one-point perspective, the contrast is easily extended and inflated into broad opposition — between Western modernity and Japanese postmodernity.

Oddly, however, whereas Cartesianism is commonly considered to be a structure or even regime of perception, those who celebrate superflat have tended to avoid associating with a structure or regime. Instead they tend to highlight its resistance to classical Western modernity and to avoid thinking in terms of socio-historical implications or power formations. As a result, superflat risks falling into a simplistic opposition between Western modernity and Japanese postmodernity in which Western modernity (Cartesianism) stands for rationality, instrumentality, and technological and perceptual mastery over the world, while Japanese postmodernity appears somewhat innocent and innocuous, free of power effects. In the first exhibit, superflat is associated with scanning, with information technologies, and the digital, which implies that there is another kind of technological condition at stake. But on the whole superflat appears unconcerned with anything but aesthetics of flatness in Japanese popular culture.

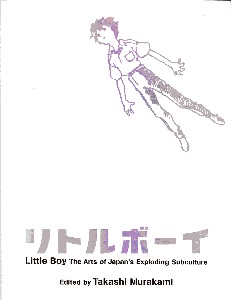

Perhaps to address this issue more directly, in the third superflat exhibit called “Little Boys,” Murakami Takashi associates manga, anime, and Japanese ‘subculture’ or otaku art with a fascination with war. He claims that such arts express a sense of inferiority vis-à-vis the American military power on the part of a generation of Japanese boys due to Japan’s defeat in WWII. They felt like ‘little boys.’ Yet these little boys remained fascinated with military power itself, especially as embodied in the atomic bomb, such as the one dropped on Hiroshima that the Americans dubbed ‘Little Boy.’ One of the goals of superflat then is to grapple with this legacy.

There are a number of problems with this way of addressing of the implications of a perceptual regime. But the major problem is that it avoids the issue. It projects the question of technology onto the mentality or psychology of youth in Japan rather than taking a serious look at technics, perception, and power. In effect, young people are blamed, and the superflat ‘movement’ is able to lay claim to their art and activities without accounting for its own interests and technics.

This is why I wish to look at the structure implicated in superflat art. It is in this way that we can ask whether a new sort of ‘perceptual regime’ is emerging in the context of the flattening of the layers of the image.